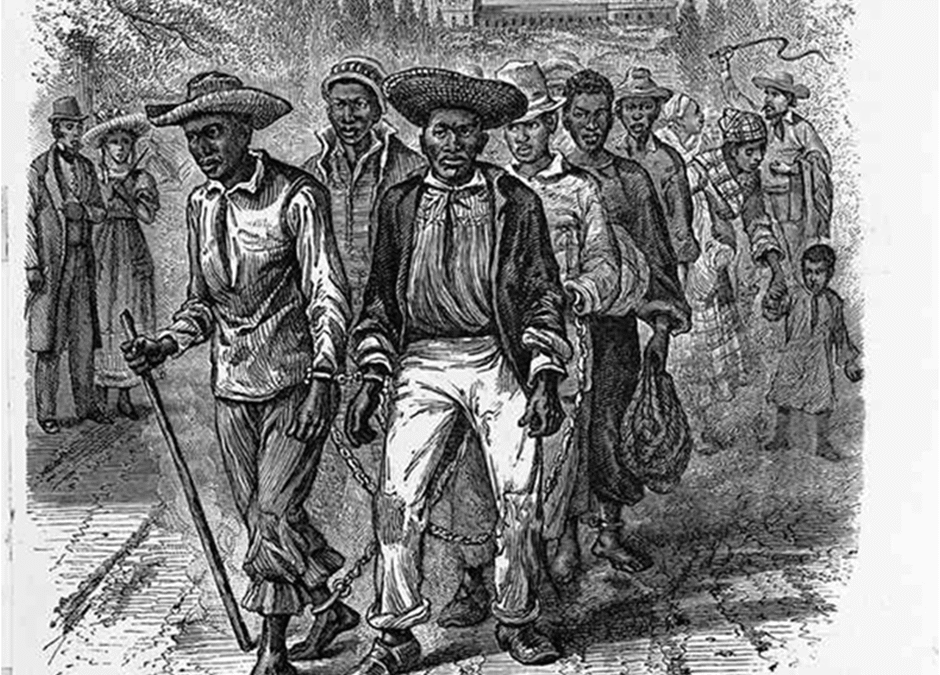

FROM AROUND 1790 TO the 1860s, millions of American settlers moved westwards and southwards from the depleted soils of Virginia and South Carolina. They moved to Alabama, Tennessee, Mississippi, Florida, Louisiana, Arkansas, and Texas. During this migration, especially between 1830 and 1850, slave coffles were a regular sight. The slaves walked from two hundred to more than a thousand miles. About six hundred thousand slaves were moved around this way and on ships.

Slaves moved to new frontiers with their owners, or they were headed for designated markets, but they could be bought from or sold to a passing coffle. Many slaves could not make it all the way and died from exhaustion, disease, hunger, or depression. Some escaped. On these long marches, children and treasured slaves, especially those tinctured with Anglo-Saxon blood like female quadroons destined for the flesh markets, would be given passage on wagons or carriages so that on arrival they fetched a good price.

It was not unusual to have pregnant slaves in the coffles, and some delivered on the long, arduous journey. Newly-borns were likely to slow down the coffle, and that could reduce the profitability of the whole venture. Often, the new-born babies would not be spared and would be given away for free or sold for a few dollars. Almost certainly, other infants must have suffered a worse fate. Of course, the feelings of the mother were inconsequential. Millions of years of evolution had conditioned hominids to look after their young. Such innate feelings did not go away just because one was a slave-mother. Interestingly, the white slaving class in America believed that Negro mothers did not have the same maternal feelings for their children that white mothers had.

Wow.

In the coffles, the men would be handcuffed right hand to left hand in twos, and a chain passed from one couple to the next down the line. The women were similarly enchained. Sometimes women would be tied together with a rope fitted around the neck like a halter, the thing put around a horse’s neck.

At times, the slaves would be forced to sing to the accompaniment of banjos and fiddles. For some, this music would be deja vu, reminiscent of their forced exercises on board slave ships during the Middle Passage. For others, this would be the second coffle, the first having been in Africa, similarly enchained or yoked, on the marches to the coast.

The journey to the southern states was also called the middle passage. Like its Atlantic counterpart, this was also a journey of untold misery that 289 Slave-Coffles in America delivered the slaves to a final destination that often took them to a very early grave. Apart from slave coffles, slaves were transported by ship from seaport to seaport, or on rivers from river-port to river-port. Slaves taken on ships and boats were insured as cargo with similar exclusions. However, since this cargo inhaled oxygen and breathed out carbon dioxide there were special exclusions like insurrection, elopement, suicide, and natural death. After the arduous walk, the slaves would be rested and fattened for a while, so as to fetch a good price at the auctions.

Then came the railroads. Sending the slaves south in slave rail wagons was much cheaper than sending them by coffles for weeks. The railways resulted in more profit for the slave traders. More money was music to the slaveholders’ ears.